|

Chapter Reference

|

Image Size

|

Mini Image

|

Image Description and Link

|

|

Chapter 1

Problem Families

Page 14

|

32KB |

|

Dr. Albert Priddy, 1924

Priddy became the superintendent of the new State Colony on April 15, 1910.

|

|

Page 19

|

7.61MB |

|

Aubrey Strode, circa 1905

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/73/

Aubrey Strode was one politician who understood this formula for local prosperity. In 1905, as a new member of the Virginia Senate, he found a use for arguments that favored building a colony in his legislative district.

|

|

Chapter 2

Sex and Surgery

Page 22

|

147KB |

|

Pennsylvania Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker, circa 1900

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/71/

Pennypacker, a former judge known for his pointed wit, rejected the "Act for the Prevention of Idiocy." If legislation alone would prevent idiocy, he argued, all civilized countries would have long since changed their laws.

|

|

Chapter 5

The Mallory Case

Page 68

|

271KB |

|

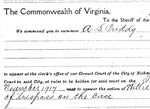

Summons ordering Dr. Priddy to appear in court for the Mallory lawsuit

(October, 1917)

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/17/

. . . before long, Priddy returned home to find a subpoena nailed to his front door.

|

|

Chapter 6

Laughlin’s Book

Page 78

|

33KB |

|

Harry H. Laughlin, circa 1920

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/64/

By 1920, Harry Laughlin had established an international reputation as an expert on eugenic sterilization. Governments as far away as Germany consulted him for information on U.S. sterilization practices.

|

|

Page 88

|

2MB |

|

Cover: Eugenical Sterilization in the United States (1922)

The statue on the book’s cover was entitled Heredity: Fountain of the Ages, created by sculptor Charles Haag

|

|

Chapter 9

Carrie Buck versus Dr. Priddy

Page 112

|

231KB |

|

Amherst County Courthouse

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/50/

As they made their way up the brick walkway to the County Courthouse, each visitor saw the obelisk placed by the Daughters of the Confederacy to honor the "sons of Amherst County" who had fallen in the Civil War a generation earlier. The plaque stood as a reminder of the sacrifices citizens are sometimes asked to make for the good of the community.

|

|

Page 116

|

181KB |

|

John T. Dobbs (on the right)

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/63/

Carrie's pregnancy was a threatening prospect for the Dobbses. John T. Dobbs did maintenance work on the city streetcar line, and his wife took in foster children. Their modest house backed up to the railroad tracks, where poor whites lived in a racially mixed neighborhood.

|

|

Page 120

|

36KB |

|

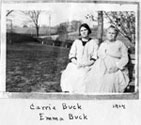

Carrie and Emma Buck, just before trial, November 1924

All of the witnesses from Charlottesville left a generally negative impression about Carrie Buck and her family. Carrie's background was poor, she was poorly behaved and poor in looks. Though not demonstrably mentally ill, like some of her relatives she seemed somehow "peculiar." Her foster parents had wanted her sent away because of the shame of her pregnancy.

|

|

P 133

|

291KB |

|

Plaque on Colony Building

Irving Whitehead knew these patients too, Priddy said. Whitehead interrupted to clarify the record: "Yes, put in there that I know them through being a member of the Special Board of Directors." In fact, only a few months before Carrie Buck's trial, a building had been completed at the Colony and named in Whitehead's honor.

|

|

Chapter 10

Defenseless

Page 144

|

40KB |

|

Alice Dobbs holding Vivian Buck, November 1924

It was Estabrook's habit to photograph the subjects of his eugenical family studies, and one surviving photo shows Alice Dobbs holding Carrie's baby. It appears that Mrs. Dobbs is holding a coin in front of Vivian's face in an attempt to catch her attention. The baby looks past her, staring into the distance, apparently failing the test. Estabrook described that moment during his testimony at trial a few days later: "I gave the child the regular mental test for a child of the age of six months, and judging from her reaction to the tests I gave her, I decided she was below the average."

|

|

Chapter 12

In the Supreme Court

Page 157

|

836KB |

|

Old Chambers, United States Supreme Court

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/72/

As Strode predicted, the final act in the Buck legal drama played out before the U.S. Supreme Court. The case was accepted for review in September 1926, and both lawyers prepared new briefs. Strode repeated the arguments he had made previously, paying particular attention to the use of state police power to enforce eugenical laws.

|

|

Page 158

|

93KB |

|

Chief Justice William Howard Taft

The men who would ultimately determine Carrie Buck's fate were led by Chief Justice William Howard Taft, the only former president of the United States who also served on the nation's highest tribunal. But like Theodore Roosevelt, who preceded him as president, and Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover to follow, Taft supported some eugenic reforms. And for more than thirty years, Taft lent his public support to some of the most prominent leaders of the eugenics movement.

|

|

Page 171

|

69KB |

|

Supreme Court Justice Pierce Butler

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/69/

Following the Holmes opinion, the Supreme Court decision was printed with only one line more: "Mr. Justice Butler dissents." There had been pressure on the Court to avoid dissents, and even when he felt compelled to register his disagreement with the majority of his colleagues, Justice Pierce Butler was not in the habit of amplifying discord in writing.

|

|

Chapter 14

After the Supreme Court

Page 185

|

228KB |

|

Virginia Colony Building where Carrie Buck was sterilized

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/57/

On the morning of October 19, 1927, Carrie Buck was taken to the infirmary of the Colony. At nine thirty, she was given drugs to prepare her for sterilization. At ten o'clock she entered the operating room fortified with morphine, to blunt the inevitable pain, and atropine, to decrease salivation. Nurse Roxie Berry gave Carrie ether to render her unconscious. After the anesthetic had taken effect, the operation began.

|

|

Page 189

|

695KB |

|

Carrie Buck and William Eagle, 1932

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/68/

"I am married and getting along alright so far. I married Mr. Eagle a man I had been going with for three years. . . . He is a good man. I thought it was best for me to marry. . . . Tell my mother I will send her something when I can."

Carrie Eagle, Bland, Va.

|

|

Page 195

|

20KB |

|

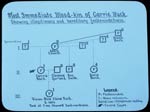

Harry Laughlin Slide of Buck Pedigree, 1929

Laughlin described the legislative history of the Virginia law and reprinted its text. He summarized the testimony at the Buck hearing and subsequent trial, repeating generous portions of his own deposition. Then he crafted a special pedigree chart showing evidence presented at the Buck trial describing the "Most immediate Blood Kin of Carrie Buck, Showing illegitimacy and hereditary feeblemindedness."

|

|

Page 211

|

560KB |

|

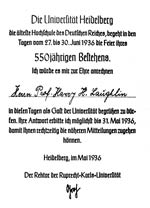

Honorary Degree Invitation to Harry Laughlin, 1936

The University of Heidelberg was planning a celebration commemorating its 550th anniversary, and Laughlin was chosen by the Nazi administrators there to receive the honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine for his work in the "science of racial cleansing."

|

|

Chapter 15

Sterilizing Germans

Page 216

|

223KB |

|

Virginia Colony Cemetery

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/58/

|

| 275KB |

|

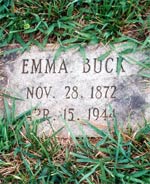

Emma Buck’s Grave

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/61/

Emma Buck died on April 15, 1944, of bronchial pneumonia. She was seventy-one years old. The final notation in her medical record was made nearly two weeks after her death, when Carrie and her brother Roy traveled to the Colony for a visit. When the superintendent failed to receive a response to the telegram he had sent to notify Carrie, he went ahead with the burial at the Colony cemetery. Only afterward did Emma's children arrive.

|

|

Page 217

|

259KB |

|

Aubrey Strode Home "Kenmore"

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/43/

|

| 274KB |

|

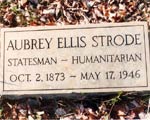

Aubrey Strode Grave

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/44/

Strode spent his last four years at his family estate, and on May 17, 1946, he died in the house where he had been born almost three quarters of a century earlier. He was eulogized in the hometown newspaper as "A Humanist on the Bench." Strode was buried in the Amherst village cemetery, only a few steps from the grave of his friend Irving Whitehead.

|

|

Chapter 16

Skinner v. Oklahoma

Page 224

|

21KB |

|

Jack Skinner before Skinner v. Oklahoma

Officials quickly identified another man who would more willingly represent the convict population. Jack Skinner worked as a prison clerk…. He had attended college, and despite his prison career, he had hopes of being a responsible parent with children of his own when he left the penitentiary.

|

|

Chapter 18

Rediscover-ing Buck

Page 250

|

254KB |

|

Carrie Buck Charlottesville Home

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/54/

Dr. John Bell had boasted about the benefits of sterilization to Carrie, saying that after surgery "she was immediately returned to society and made good." But in 1980 she was living in a cinderblock shed in a muddy field just north of Charlottesville, Virginia. Her life had been defined by constant and sometimes abject poverty.

|

|

Page 253

|

443KB |

|

Doris and Matthew Figgins, 1980

Though she was not listed under her real name in the lawsuit, the most prominent victim of sterilization was also the plaintiff who had been sterilized first, when she was thirteen years old. Doris Buck joined the suit to redress the fifty-year-old cloud over her family name.

|

|

Page 254

|

221KB |

|

District home in Waynesboro

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/55/

|

| |

|

Carrie Buck, 1982

In 1982 Doris Buck died. Within six months, her sister Carrie was also at death's door. I met Carrie Buck while she was living in the "District Home," a rural facility near Waynesboro, Virginia, that had been constructed in 1927 to replace county almshouses. It eventually was transformed into a retirement community for indigent seniors.

|

|

Page 256

|

307KB |

|

Carrie Buck and husband Charlie Detamore

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/52/

Carrie's grave was placed near a maple tree beside the cemetery drive. The plot that later also accommodated her husband Charlie was marked that day only with a small tin nameplate.

|

|

256

|

287KB |

|

Paul Lombardo at Buck Grave

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/51/

|

|

258

|

22KB |

|

Mitch Van Yahres in Virginia General Assembly, 2001

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/67/

Mitch Van Yahres, who represented the city of Charlottesville in the Virginia House of Delegates, introduced a resolution "Expressing Regret for Virginia's Experience with Eugenics."

|

|

263

|

115KB |

|

Buck Marker Charlottesville, Author with survivors, 2002

http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/buckvbell/66/

In Carrie Buck's hometown of Charlottesville, a short drive from the cemetery where she was buried, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources erected a marker just around the corner from the school Buck's daughter Vivian attended.

|

|

265

|

39KB |

|

Linda Sparkman and Indiana Eugenics Marker, 2007

2007 marked the centennial of the 1907 Indiana sterilization law, the first of its kind in the world. A state historic marker describing the now-defunct eugenics laws was unveiled by Linda Sparkman, plaintiff in the 1978 Supreme Court case challenging her own extra-legal sterilization.

|